Three out of four preserved Norwegian Viking ships have been discovered in our county Vestfold.

By Einar Chr. Erlingsen – Chair of the Oseberg Viking Heritage Foundation

The Viking ships did not appear out of nowhere, but were the results of a development over thousands of years. Even so, until 1880 AD we had only vague perceptions of what they had actually looked like. In pre 1880 art we see them depicted in rather fanciful ways, including ducktail sterns.

The answers to what the Viking ships had actually looked like were buried in Vestfold´s rich soil. Even before the excavation of the Gokstad ship some clues had been detected, namely the Borre ship (1852) and the Tune ship (1867). However, not enough of either ship was preserved to offer any real insight.

Only with the Gokstad (1880), Klastad (1893 – excavated 1970) and Oseberg (1904) did the world get solid facts. It´s no exaggeration that the finds from Vestfold alone have meant more for our understanding of the Viking ships than all the world´s other Viking ships combined.

We learnt a lot more as well. This is especially true regarding the most impressive find of them all; the Oseberg. It is not possible to exaggerate its importance; it ranks among the very top of the world´s most important archaeological finds – ever. The Oseberg is as important for the understanding of the Viking world as the detection of Tut-Ankh-Amon´s untouched grave a few decades later was for the understanding of ancient Egypt. For the very first time we got a glimpse into a hitherto unknown female world – attached to ships.

Oseberg and Gokstad are renowned for their splendour and were undoubtedly built for showing off. They had room for large crews – but little for cargo. This is reversed on the Klastad, which was built for carrying huge quantities of cargo and livestock, but with a crew of perhaps only six or eight. Oseberg and Gokstad could both be rowed or sailed, while the Klastad had to await favourable wind before setting off.

Norway was in the middle of a nationalistic upsurge when the Gokstad and Oseberg were excavated. The country was getting ready to leave the forced union with Sweden. It was important to demonstrate that also we had a proud history. So it made sense to locate the great ships in a museum in the nation´s capital. In 1970 however, it was no longer considered of national importance to move the Klastad to Oslo, so she was allowed to remain in Vestfold and can be seen today at the Slottsfjell Museum in Tonsberg.

Klastad, along with a.o. the five Skuldelev ships from the Roskilde Fjord (excavated 1962) in Denmark, added to our understanding that there were many types of Viking ships, each type with their specific use, construction and characteristics.

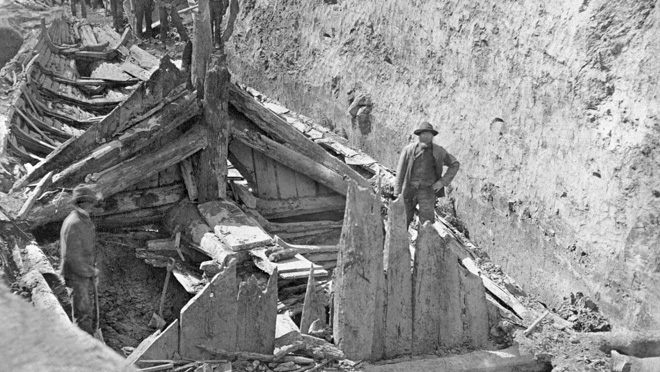

Only with the discovery of the Gokstad ship did the world learn what a Viking ship looked like. Soon, new discoveries in county Vestfold would reveal different ship types – and that they were results of a process over several thousand years. (Photo: Cultural History Museum/UiO).

The Soerum boat is the oldest boat found in Norway so far. It was carved out of one single trunk. Experiments with replicas have shown the boat to be far easier to manoeuvre than previously thought. (Photo: The Wilderness Camp).

Board Vice Chair Knut Børge Knutsen at Oseberg Viking Heritage Foundation points out some enormous Bronze Age ship carvings. (Photo: Einar Chr. Erlingsen).

Stone Age and Bronze Age boats

With the ships from Vestfold and other finds that we shall return to, it has become obvious that the Viking ships have very long roots within Nordic history.

The first Scandinavians probably used a trunk from a tree for crossing a river or lake. Soon they discovered that the voyage would be safer and easier if they latched several trunks together. The result was a fleet; steady, but also heavy and difficult to manoeuvre.

The next step in the long process appeared when someone came upon the idea of hollowing out a trunk. This was no less than a revolution; a trunk boat was both easier to steer and could be used over longer distances. The oldest stock boat discovered in Scandinavia is from Denmark and approximately 6.000 years old. In Norway, the Soerum boat is the oldest one, some 2.200 years. But there is no reason to think that the stock boat not has a much longer history even here.

Our forefathers soon detected that stability was improved by leaving props at regular intervals when carving out a trunk. The ribs and thwarts were invented! To improve both seaworthiness and load capacity even further, they soon added the first planks on top of the trunk, sewing them together by sinews or other materials. The first “clinker-built” boats had been invented.

There was one disadvantage with this new type of boat, however; they were both heavy and work consuming to build. The solution: to develop the canoe! The ribs were kept, while the trunk was replaced by an outer skin made out of hides, bark from birch trees or similar. Today, boat builders in Norway still use the same words; saum (from sewing) and hud (skin) when talking about rivets and hull planks. The materials have changed, while the words have remained.

Next, the canoe inspired similar clinker-built constructions, built for longer voyages across water. Customised wooden planks replaced hides and bark. We can see these boats on countless Bronze Age rock carvings, frequently with their characteristic double prows. These boats could be very large. If the theory that each “stroke” symbolises one crewmember (some say two) is correct, we´re talking about big, ocean-going boats that can carry a crew of several dozen men.

Fortunately enough, one of these ships has been preserved, although of a slightly younger date. The Hjortspring Boat has been dated to BC 300-400. It was found in a Danish swamp in 1915 and is the oldest known ship built with wooden planks that we know of in our part of the world. No less than 19 meters long, the ship has probably carried a crew of some 20 men, using paddlers as “engine”. Tests with modern replicas have showed that a trained crew could reach a speed of around 8 knots on calm water, and 3,5 knots in waves. This means that they could cross from Norway to Denmark in less than 24 hours.

Drawing showing the Danish Hjortspring boat from around 300-400 BC. This is the oldest known clinker-built boat in Scandinavia. The boat could carry a crew of some 20 men. (Source: Wikipedia).

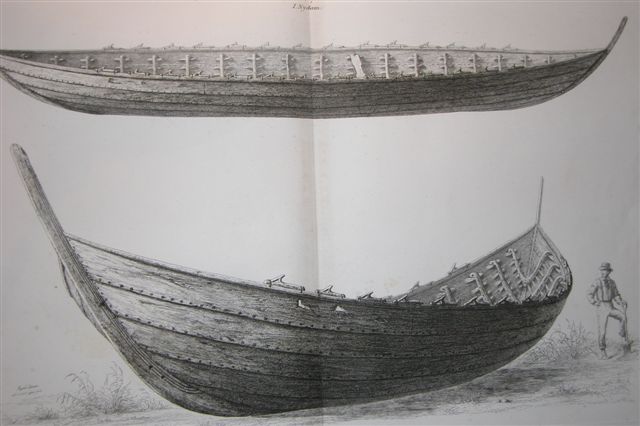

The Nydam ship is the oldest known rowing-ship in Northern Europe, dated to around 320 AD. (Photo: Erik Christensen).

A replica of the 1400 years old Sutton Hoo ship is now being built in England. (Photo: The Sutton Hoo´s Ship Company).

The Nydam ship is the oldest known rowing-ship in Northern Europe, dated to around 320 AD. (Photo: Erik Christensen).

From paddlers to oars

Then, things started to speed up even more. Exactly 500 years before the Oseberg ship was built, the Nydam ship was launched in Denmark. Once again we see a revolution; the Nydam ship (AD 320) is the oldest rowing ship known from Northern Europe. The paddlers were stowed away and replaced by oars.

The Nydam ship is pointing towards the oldest ship we know of that has been equipped with a sail; the Oseberg (AD 820). Both are clinker-built, the hull boards all have integrated “clamps” for lashing them to the ship´s ribs, using material like strips from whale baleens, tree roots etc. The same building method was used for the Gokstad (AD 900), while on the Klastad (AD 1000) the method has been replaced, using iron nails or wooden pegs in stead.

The prows of the Nydam ship proudly rise in a half-moon fashion, shaped out of one piece of wood – as on a Viking ship. Further, the rudders on both types are mounted on its starboard side. (In Norwegian, starboard literally means steering board). This in contrast to earlier types, where most agree that a paddler was used for steering.

The Nydam ship is slightly longer than Oseberg, 23 meters as compared to 21.5. We know that a ship like this could easily cross the sea between Norway and Denmark. At Illerup Ådal – a swamp outside Århus, a fantastic discovery was made around 1950; the remnants of a well-equipped army of some 1.000 men. They had lost a battle (around AD 200), and their belongings were sacrificed into the swamp. Today, most experts agree that this army originated in Norway.

The Illerup Ådal find can be seen at the Moesgaard Museum outside Århus, while the Nydam ship is on display at the Landesmuseum Schleswig-Holstein in Northern Germany.

A short visit to England

We must go to England to study the next step in development; to the windblown marshlands of East Anglia. This is where the first Anglo-Saxons settled in the early fifth century. During the next 200 years they became the country´s dominant tribe; England is the land of the Angles. They, as did the Saxons – originated in the North-western parts of what is today southern Schleswig and the border area between Denmark, Germany and The Netherlands. The sea offered their only road to the British Isles, and today we know quite well what their ships looked like. They also represent a clear, Scandinavian development and tradition.

Once, in the early years of the seventh century an Anglo-Saxon chieftain was buried at the place today known as Sutton Hoo. Much evidence point towards Raedwald, king of Norfolk and Suffolk in the years 599-624. He was buried in a great mound Scandinavian style, inside a grave chamber and surrounded by valuable artefacts. Similar burials from the same period are known both in Norway (Åker outside Hamar) and Sweden (Uppland, outside Uppsala), and point towards close connections across the North Sea.

Here, our main interest is the ship, however. Although almost all wood had rotted up when the mound was excavated in 1939, the imprint of the ship in the surrounding soil was almost perfect, making it possible to interprete.

Here I should add that a visit with some friends to Sutton Hoo in the early days of this century added much to the inspiration for building our own Viking ships. At Sutton Hoo we understood how much insight can be achieved from building archaeological replicas. We´re not just a little proud of the fact that we beat the British with a good margin; our Oseberg replica was launched in 2012, while the Sutton Hoo replica is still not finished.

The ship had been some 27 meters long, with Viking type raised prows. It was clinker-built, but without a real keel. Nor where there any sign of a mast. That would come almost 200 years later, with the ship we know today as the Oseberg.

Although much point from Nydam to Sutton Hoo to Oseberg, there is still one decisive difference: Before Oseberg there is no evidence of a fixed mast and sail being used. That is, in our part of the world. Why, is still a great mystery. Scandinavian traders, warriors and mercenaries have without doubt been in contact with the Mediterranean world, both before and after the birth of Christ. Discoveries of Roman coins and weapons from Illerup Ådal are just some out of many proofs of this contact. So why did it take so long for Scandinavians to take the sail into use?

We simply do not know. What we do know, however, is that when it finally happened, it started a revolution, one that would be felt from the steppes of Asia to the American continent. With the Viking ships, the Scandinavians were able to voyage faster, longer and more daring than anyone had ever done before them.

From the Klastad ship excavations in 1970. The Klastad was a knarr – built for carrying cargo. (Photo: Unknown).

From the building of the Klastad ship replica. (Photo: Espen Jørgensen).

Two out of three Viking ships from Vestfold have been copied by the Oseberg Viking Heritage Foundation. In 2021 we have started to build the third: Gokstad. Front: Klastad, then Oseberg. (Photo: Einar Chr. Erlingsen)

The ships from Vestfold

The three Vestfold Viking ships are very different from each other, and span a period of almost 200 years. Thus, they add to our knowledge of both ship types and technical development.

The discovery of the Gokstad ship in 1880 had created worldwide sensation. The ship was almost perfectly preserved, as was the rich grave goods discovered within.

In 1893, the Gokstad was a sensation once more, when Captain Magnus Andersen sailed a newly built copy from Norway, across the Atlantic and onto Chicago, just in time for the World Fair. The Fair, although a year too late, was dedicated to the 400 years anniversary for Columbus´ discovery of America.

So, the Klastad ship, also discovered in 1893, was soon forgotten. That is, until 1970, when the waterlogged field was to be drained. It was decided to excavate, and soon established that this ship was quite different from Oseberg and Gokstad. While these ships were built for some powerful person to “show off”, the Klastad was a typical cargo ship, designed to transport cargo over long distances and in rough seas. It was ships like Klastad that were used for crossing to Iceland, Greenland and even The Americas.

One more ship originating in Vestfold deserves to be mentioned. Just outside the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark an enormous, 36 meters long ship has been excavated. This was a ship built for speed and battle.

Wood analyses proved that the ship was built in Vestfold around AD 1025. Not many could afford a ship like this – but the sagas mention that the Norwegian King Olav Haraldsson built his ship Visund (Bison) around that time. We can´t prove that the Roskilde ship is identical with Visund – but we at know at least that also the world´s largest known Viking ship has a strong link to Vestfold.